Precision prevention

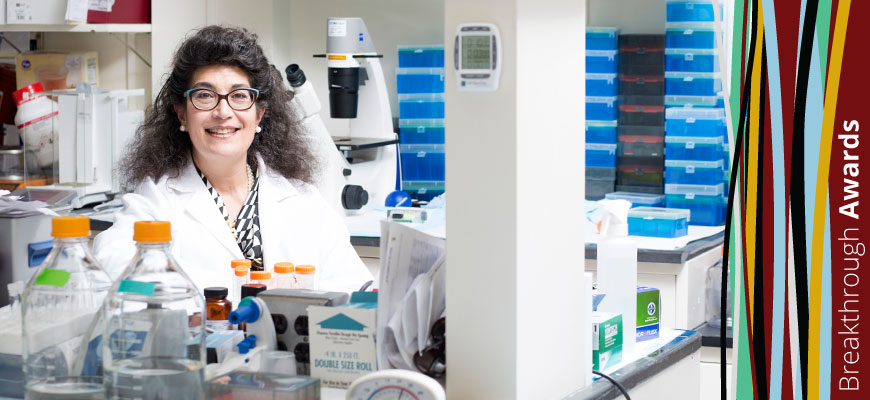

School of Medicine researcher Carole Oskeritzian offers hope for allergy sufferers

Posted on: February 24, 2017; Updated on: February 24, 2017

By Chris Horn, chorn@mailbox.sc.edu, 803-777-3687

As a child, Carole Oskeritzian nearly died from asthma attacks because of her allergies.

She remembers the struggle for breath and especially the bearded man’s face on the vials of her allergy shots. It was Louis Pasteur, namesake of the Pasteur Institute in Paris, France, which produced the medicine. Oskeritzian later worked as a tenured scientist at the Pasteur Institute before moving to the U.S. and eventually joining the USC School of Medicine Columbia.

Now she’s making important discoveries about the human immune system that could lead to new prophylactic options, bringing hope to sufferers of asthma and other serious allergic diseases. Her research is also focused on creating novel screening tests to predict serious allergic responses or even cancer later in life.

“We do not claim our research will cure eczema or asthma because those are complex chronic diseases,” says Oskeritzian, an assistant professor in the Department of Pathology, Microbiology and Immunology. “Rather, we are interested in identifying the early changes in tissues that precede the disease stage. What is happening in the lungs prior to asthma symptoms, in skin before eczema appears, in prostate or colon tissues before cancer? Our goal is to prevent rather than cure using precision prevention.”

Oskeritzian focuses on mast cells, which are at the forefront of the immune responses in a healthy human body. Located around blood vessels, mast cells possess the unique ability to generate and store many chemicals that aid in wound healing, fighting germs and venom detoxification.

But mast cells can also wreak havoc when they release histamine or become hyperreactive. Oskeritzian’s research has revealed the interplay human mast cells have with a signaling lipid called sphingosine-1-phosphate or S1P in inflammation. S1P promotes mast cell hyperreactivity.

“We discovered that human mast cells react to but also produce S1P. Mast cell-derived S1P may positively and locally influence the survival, differentiation, movement and reactivity of many cells, including inflammatory cells, cancer cells and cells composing the blood vessels,” she says.

Oskeritzian’s team utilizes several disease models and also grows primary human and mouse mast cells in vitro to study their response to allergens and other substances they may encounter. The goal is to determine the underlying mechanisms leading to symptoms.

“So we’re working on developing alternate therapeutic approaches and novel mast cell-based screening methods to predict which human subjects could develop these diseases by measuring the number and activation state of mast cells directly in tissues,” she says. “The problem is not necessarily having an increased number of mast cells but their conversion to a hyper-responsive subset.”

Oskeritzian’s research often finds its way into her lectures on medical pathology, microbiology and immunology in the form of case studies and journal articles.

“I use a lot of clinical vignettes to make the subject matter exciting, interactive and relevant — the case studies put science in context,” she says. “There’s not a single lecture where I’m not engaged in a two-way discussion with the students. I want to make sure they understand these connections.”

Share this Story! Let friends in your social network know what you are reading about